Draw Binary Tree Diagram Online

A Binary Search Tree (BST) is a binary tree in which each vertex has only up to 2 children that satisfies BST property: All vertices in the left subtree of a vertex must hold a value smaller than its own and all vertices in the right subtree of a vertex must hold a value larger than its own (we have assumption that all values are distinct integers in this visualization and small tweak is needed to cater for duplicates/non integer). Try clicking for a sample animation on searching a random value ∈ [1..99] in the random BST above.

An Adelson-Velskii Landis (AVL) tree is a self-balancing BST that maintains it's height to be O(log N) when having N vertices in the AVL tree.

Remarks: By default, we show e-Lecture Mode for first time (or non logged-in) visitor.

If you are an NUS student and a repeat visitor, please login.

→

🕑

To toggle between the standard Binary Search Tree and the AVL Tree (only different behavior during Insertion and Removal of an Integer), select the respective header.

We also have URL shortcut to quickly access the AVL Tree mode, which is https://visualgo.net/en/avl (you can change the 'en' to your two characters preferred language - if available).

Pro-tip 1: Since you are not logged-in, you may be a first time visitor (or not an NUS student) who are not aware of the following keyboard shortcuts to navigate this e-Lecture mode: [PageDown]/[PageUp] to go to the next/previous slide, respectively, (and if the drop-down box is highlighted, you can also use [→ or ↓/← or ↑] to do the same),and [Esc] to toggle between this e-Lecture mode and exploration mode.

←

→

🕑

BST (and especially balanced BST like AVL Tree) is an efficient data structure to implement a certain kind of Table (or Map) Abstract Data Type (ADT).

A Table ADT must support at least the following three operations as efficient as possible:

- Search(v) — determine if v exists in the ADT or not,

- Insert(v) — insert v into the ADT,

- Remove(v) — remove v from the ADT.

Reference: See similar slide in Hash Table e-Lecture.

Pro-tip 2: We designed this visualization and this e-Lecture mode to look good on 1366x768 resolution or larger (typical modern laptop resolution in 2021). We recommend using Google Chrome to access VisuAlgo. Go to full screen mode (F11) to enjoy this setup. However, you can use zoom-in (Ctrl +) or zoom-out (Ctrl -) to calibrate this.

←

→

🕑

We are referring to Table ADT where the keys need to be ordered (as opposed to Table ADT where the keys do not need to be unordered).

This special requirement of Table ADT will be made clearer in the next few slides.

Pro-tip 3: Other than using the typical media UI at the bottom of the page, you can also control the animation playback using keyboard shortcuts (in Exploration Mode): Spacebar to play/pause/replay the animation, ←/→ to step the animation backwards/forwards, respectively, and -/+ to decrease/increase the animation speed, respectively.

←

→

🕑

If we use unsorted array/vector to implement Table ADT, it can be inefficient:

- Search(v) runs in O(N), as we may end up exploring all N elements of the ADT if v actually does not exist,

- Insert(v) can be implemented in O(1), just put v at the back of the array,

- Remove(v) runs in O(N) too as we have to first search for v which is already O(N) and later close the resulting gap after deletion — also in O(N).

←

→

🕑

If we use sorted array/vector to implement Table ADT, we can improve the Search(v) performance but weakens the Insert(v) performance:

- Search(v) can now be implemented in O(log N), as we can now use binary search on the sorted array,

- Insert(v) now runs in O(N) as we need to implement an insertion-sort like strategy to make the array remains sorted,

- Remove(v) runs in O(N) because even if Search(v) runs in O(log N), we still need to close the gap after deletion — which is in O(N).

←

→

🕑

The goal for this e-Lecture is to introduce BST and then balanced BST (AVL Tree) data structure so that we can implement the basic Table ADT operations: Search(v), Insert(v), Remove(v), and a few other Table ADT operations — see the next slide — in O(log N) time — which is much smaller than N.

PS: Some of the more experienced readers may notice that ∃ another data structure that can implement the three basic Table ADT operations in faster time, but read on...

| N | ≈ 1 000 | ≈ 1 000 000 | ≈ 1 000 000 000 |

| log N | 10 | Only 20 :O | Only 30 :O:O |

←

→

🕑

On top of the basic three, there are a few other possible Table ADT operations:

- Find the Min()/Max() element,

- Find the Successor(v) — 'next larger'/Predecessor(v) — 'previous smaller' element,

- List elements in sorted order,

- Operation X & Y - hidden for pedagogical purpose in an NUS module,

- There are others possible operations.

Discussion: What are the best possible implementation for the first three additional operations if we are limited to use [sorted|unsorted] array/vector?

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

The simpler data structure that can be used to implement Table ADT is Linked List.

Quiz: Can we perform all basic three Table ADT operations: Search(v)/Insert(v)/Remove(v) efficiently (read: faster than O(N)) using Linked List?

Discussion: Why?

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

Another data structure that can be used to implement Table ADT is Hash Table. It has very fast Search(v), Insert(v), and Remove(v) performance (all in expected O(1) time).

Quiz: So what is the point of learning this BST module if Hash Table can do the crucial Table ADT operations in unlikely-to-be-beaten expected O(1) time?

Discuss the answer above! Hint: Go back to the previous 4 slides ago.

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

We will now introduce BST data structure. See the visualization of an example BST above!

Root vertex does not have a parent. There can only be one root vertex in a BST. Leaf vertex does not have any child. There can be more than one leaf vertex in a BST. Vertices that are not leaf are called the internal vertices. Sometimes root vertex is not included as part of the definition of internal vertex as the root of a BST with only one vertex can actually fit into the definition of a leaf too.

In the example above, vertex 15 is the root vertex, vertex {5, 7, 50} are the leaves, vertex {4, 6, 15 (also the root), 23, 71} are the internal vertices.

←

→

🕑

Each vertex has at least 4 attributes: parent, left, right, key/value/data (there are potential other attributes). Not all attributes will be used for all vertices, e.g. the root vertex will have its parent attribute = NULL. Some other implementation separates key (for ordering of vertices in the BST) with the actual satellite data associated with the keys.

The left/right child of a vertex (except leaf) is drawn on the left/right and below of that vertex, respectively. The parent of a vertex (except root) is drawn above that vertex. The (integer) key of each vertex is drawn inside the circle that represent that vertex. In the example above, (key) 15 has 6 as its left child and 23 as its right child. Thus the parent of 6 (and 23) is 15.

←

→

🕑

As we do not allow duplicate integer in this visualization, the BST property is as follow: For every vertex X, all vertices on the left subtree of X are strictly smaller than X and all vertices on the right subtree of X are strictly greater than X.

In the example above, the vertices on the left subtree of the root 15: {4, 5, 6, 7} are all smaller than 15 and the vertices on the right subtree of the root 15: {23, 50, 71} are all greater than 15. You can recursively check BST property on other vertices too.

For more complete implementation, we should consider duplicate integers too. The easiest way to support this is to add one more attribute at each vertex: the frequency of occurrence of X (this visualization will be upgraded with this feature soon).

←

→

🕑

We provide visualization for the following common BST/AVL Tree operations:

- Query operations (the BST structure remains unchanged):

- Search(v),

- Predecessor(v) (and similarly Successor(v)), and

- Inorder Traversal (we will add Preorder and Postorder Traversal soon),

- Update operations (the BST structure may likely change):

- Insert(v),

- Remove(v), and

- Create BST (several criteria).

←

→

🕑

There are a few other BST (Query) operations that have not been visualized in VisuAlgo:

- Rank(v): Given a key v, determine what is its rank (1-based index) in the sorted order of the BST elements. That is, Rank(FindMin()) = 1 and Rank(FindMax()) = N. If v does not exist, we can report -1.

- Select(k): Given a rank k, 1 ≤ k ≤ N, determine the key v that has that rank k in the BST. Or in another word, find the k-th smallest element in the BST. That is, Select(1) = FindMin() and Select(N) = FindMax().

The details of these two operations are currently hidden for pedagogical purpose in a certain NUS module.

←

→

🕑

Data structure that is only efficient if there is no (or rare) update, especially the insert and/or remove operation(s) is called static data structure.

Data structure that is efficient even if there are many update operations is called dynamic data structure. BST and especially balanced BST (e.g. AVL Tree) are in this category.

←

→

🕑

Because of the way data (distinct integers for this visualization) is organised inside a BST, we can binary search for an integer v efficiently (hence the name of Binary Search Tree).

First, we set the current vertex = root and then check if the current vertex is smaller/equal/larger than integer v that we are searching for. We then go to the right subtree/stop/go the left subtree, respectively. We keep doing this until we either find the required vertex or we don't.

On the example BST above, try clicking (found after 2 comparisons), (found after 3 comparisons), (not found after 3 comparisons).

←

→

🕑

Similarly, because of the way data is organised inside a BST, we can find the minimum/maximum element (an integer in this visualization) by starting from root and keep going to the left/right subtree, respectively.

Try clicking and on the example BST shown above. The answers should be 4 and 71 (both after 4 comparisons).

←

→

🕑

Search(v)/FindMin()/FindMax() operations run in O(h) where h is the height of the BST.

But note that this h can be as tall as O(N) in a normal BST as shown in the random 'skewed right' example above. Try (this value should not exist as we only use random integers between [1..99] to generate this random BST and thus the Search routine should check all the way from root to the only leaf in O(N) time — not efficient.

←

→

🕑

Because of the BST properties, we can find the Successor of an integer v (assume that we already know where integer v is located from earlier call of Search(v)) as follows:

- If v has a right subtree, the minimum integer in the right subtree of v must be the successor of v. Try (should be 50).

- If v does not have a right subtree, we need to traverse the ancestor(s) of v until we find 'a right turn' to vertex w (or alternatively, until we find the first vertex w that is greater than vertex v). Once we find vertex w, we will see that vertex v is the maximum element in the left subtree of w. Try (should be 15).

- If v is the maximum integer in the BST, v does not have a successor. Try (should be none).

←

→

🕑

The operations for Predecessor of an integer v are defined similarly (just the mirror of Successor operations).

Try the same three corner cases (but mirrored): (should be 5), (should be 23), (should be none).

At this point, stop and ponder these three Successor(v)/Predecessor(v) cases to ensure that you understand these concepts.

←

→

🕑

Predecessor(v) and Successor(v) operations run in O(h) where h is the height of the BST.

But recall that this h can be as tall as O(N) in a normal BST as shown in the random 'skewed right' example above. If we call , we will go up from that last leaf back to the root in O(N) time — not efficient.

←

→

🕑

We can perform an Inorder Traversal of this BST to obtain a list of sorted integers inside this BST (in fact, if we 'flatten' the BST into one line, we will see that the vertices are ordered from smallest/leftmost to largest/rightmost).

Inorder Traversal is a recursive method whereby we visit the left subtree first, exhausts all items in the left subtree, visit the current root, before exploring the right subtree and all items in the right subtree. Without further ado, let's try to see it in action on the example BST above.

←

→

🕑

Inorder Traversal runs in O(N), regardless of the height of the BST.

Discussion: Why?

PS: Some people call insertion of N unordered integers into a BST in O(N log N) and then performing the O(N) Inorder Traversal as 'BST sort'. It is rarely used though as there are several easier-to-use (comparison-based) sorting algorithms than this.

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

We have not included the animation of these two other classic tree traversal methods, but we will do so very soon.

But basically, in Preorder Traversal, we visit the current root before going to left subtree and then right subtree. For the example BST shown in the background, we have: {{15}, {6, 4, 5, 7}, {23, 71, 50}}. PS: Do you notice the recursive pattern? root, members of left subtree of root, members of right subtree of root.

In Postorder Traversal, we visit the left subtree and right subtree first, before visiting the current root. For the example BST shown in the background, we have: {{5, 4, 7, 6}, {50, 71, 23}, {15}}.

←

→

🕑

We can insert a new integer into BST by doing similar operation as Search(v). But this time, instead of reporting that the new integer is not found, we create a new vertex in the insertion point and put the new integer there. Try on the example above.

←

→

🕑

Insert(v) runs in O(h) where h is the height of the BST.

By now you should be aware that this h can be as tall as O(N) in a normal BST as shown in the random 'skewed right' example above. If we call , i.e. we insert a new integer greater than the current max, we will go from root down to the last leaf and then insert the new integer as the right child of that last leaf in O(N) time — not efficient (note that we only allow up to h=9 in this visualization).

←

→

🕑

Quiz: Inserting integers [1,10,2,9,3,8,4,7,5,6] one by one in that order into an initially empty BST will result in a BST of height:

Pro-tip: You can use the 'Exploration mode' to verify the answer.

←

→

🕑

We can remove an integer in BST by performing similar operation as Search(v).

If v is not found in the BST, we simply do nothing.

If v is found in the BST, we do not report that the existing integer v is found, but instead, we perform one of the three possible removal cases that will be elaborated in three separate slides (we suggest that you try each of them one by one).

←

→

🕑

The first case is the easiest: Vertex v is currently one of the leaf vertex of the BST.

Deletion of a leaf vertex is very easy: We just remove that leaf vertex — try on the example BST above (second click onwards after the first removal will do nothing — please refresh this page or go to another slide and return to this slide instead).

This part is clearly O(1) — on top of the earlier O(h) search-like effort.

←

→

🕑

The second case is also not that hard: Vertex v is an (internal/root) vertex of the BST and it has exactly one child. Removing v without doing anything else will disconnect the BST.

Deletion of a vertex with one child is not that hard: We connect that vertex's only child with that vertex's parent — try on the example BST above (second click onwards after the first removal will do nothing — please refresh this page or go to another slide and return to this slide instead).

This part is also clearly O(1) — on top of the earlier O(h) search-like effort.

←

→

🕑

The third case is the most complex among the three: Vertex v is an (internal/root) vertex of the BST and it has exactly two children. Removing v without doing anything else will disconnect the BST.

Deletion of a vertex with two children is as follow: We replace that vertex with its successor, and then delete its duplicated successor in its right subtree — try on the example BST above (second click onwards after the first removal will do nothing — please refresh this page or go to another slide and return to this slide instead).

This part requires O(h) due to the need to find the successor vertex — on top of the earlier O(h) search-like effort.

←

→

🕑

This case 3 warrants further discussions:

- Why replacing a vertex B that has two children with its successor C is always a valid strategy?

- Can we replace vertex B that has two children with its predecessor A instead? Why or why not?

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

Remove(v) runs in O(h) where h is the height of the BST. Removal case 3 (deletion of a vertex with two children is the 'heaviest' but it is not more than O(h)).

As you should have fully understand by now, h can be as tall as O(N) in a normal BST as shown in the random 'skewed right' example above. If we call , i.e. we remove the current max integer, we will go from root down to the last leaf in O(N) time before removing it — not efficient.

←

→

🕑

To make life easier in 'Exploration Mode', you can create a new BST using these options:

- Empty BST (you can then insert a few integers one by one),

- The two e-Lecture Examples that you may have seen several times so far,

- Random BST (which unlikely to be extremely tall),

- Skewed Left/Right BST (tall BST with N vertices and N-1 linked-list like edges, to showcase the worst case behavior of BST operations; disabled in AVL Tree mode).

←

→

🕑

We are midway through the explanation of this BST module. So far we notice that many basic Table ADT operations run in O(h) and h can be as tall as N-1 edges like the 'skewed left' example shown — inefficient :(...

So, is there a way to make our BSTs 'not that tall'?

PS: If you want to study how these basic BST operations are implemented in a real program, you can download this BSTDemo.cpp.

←

→

🕑

At this point, we encourage you to press [Esc] or click the X button on the bottom right of this e-Lecture slide to enter the 'Exploration Mode' and try various BST operations yourself to strengthen your understanding about this versatile data structure.

When you are ready to continue with the explanation of balanced BST (we use AVL Tree as our example), press [Esc] again or switch the mode back to 'e-Lecture Mode' from the top-right corner drop down menu. Then, use the slide selector drop down list to resume from this slide 12-1.

←

→

🕑

We have seen from earlier slides that most of our BST operations except Inorder traversal runs in O(h) where h is the height of the BST that can be as tall as N-1.

We will continue our discussion with the concept of balanced BST so that h = O(log N).

←

→

🕑

There are several known implementations of balanced BST, too many to be visualized and explained one by one in VisuAlgo.

We focus on AVL Tree (Adelson-Velskii & Landis, 1962) that is named after its inventor: Adelson-Velskii and Landis.

Other balanced BST implementations (more or less as good or slightly better in terms of constant-factor performance) are: Red-Black Tree, B-trees/2-3-4 Tree (Bayer & McCreight, 1972), Splay Tree (Sleator and Tarjan, 1985), Skip Lists (Pugh, 1989), Treaps (Seidel and Aragon, 1996), etc.

←

→

🕑

To facilitate AVL Tree implementation, we need to augment — add more information/attribute to — each BST vertex.

For each vertex v, we define height(v): The number of edges on the path from vertex v down to its deepest leaf. This attribute is saved in each vertex so we can access a vertex's height in O(1) without having to recompute it every time.

←

→

🕑

Formally:

v.height = -1 (if v is an empty tree)

v.height = max(v.left.height, v.right.height) + 1 (otherwise)

The height of the BST is thus: root.height.

On the example BST above, height(11) = height(32) = height(50) = height(72) = height(99) = 0 (all are leaves). height(29) = 1 as there is 1 edge connecting it to its only leaf 32.

←

→

🕑

Quiz: What are the values of height(20), height(65), and height(41) on the BST above?

height(65) = 3

height(20) = 2

height(41) = 3

height(65) = 2

height(41) = 4

height(20) = 3

←

→

🕑

If we have N elements/items/keys in our BST, the lower bound height h > log2 N if we can somehow insert the N elements in perfect order so that the BST is perfectly balanced.

See the example shown above for N = 15 (a perfect BST which is rarely achievable in real life — try inserting any other integer and it will not be perfect anymore).

←

→

🕑

N ≤ 1 + 2 + 4 + ... + 2h

N ≤ 20 + 21 + 22 + … + 2h

N < 2h+1 (sum of geometric progression)

log2 N < log2 2h+1

log2 N < (h+1) * log2 2 (log2 2 is 1)

h > (log2 N)-1 (algebraic manipulation)

h > log2 N

←

→

🕑

If we have N elements/items/keys in our BST, the upper bound height h < N if we insert the elements in ascending order (to get skewed right BST as shown above).

The height of such BST is h = N-1, so we have h < N.

Discussion: Do you know how to get skewed left BST instead?

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

We have seen that most BST operations are in O(h) and combining the lower and upper bounds of h, we have log2 N < h < N.

There is a dramatic difference between log2 N and N and we have seen from the discussion of the lower bound that getting perfect BST (at all times) is near impossible...

So can we have BST that has height closer to log2 N, i.e. c * log2 N, for a small constant factor c? If we can, then BST operations that run in O(h) actually run in O(log N)...

←

→

🕑

Introducing AVL Tree, invented by two Russian (Soviet) inventors: Georgy Adelson-Velskii and Evgenii Landis, back in 1962.

In AVL Tree, we will later see that its height h < 2 * log N (tighter analysis exist, but we will use easier analysis in VisuAlgo where c = 2). Therefore, most AVL Tree operations run in O(log N) time — efficient.

Insert(v) and Remove(v) update operations may change the height h of the AVL Tree, but we will see rotation operation(s) to maintain the AVL Tree height to be low.

←

→

🕑

To have efficient performance, we shall not maintain height(v) attribute via the O(N) recursive method every time there is an update (Insert(v)/Remove(v)) operation.

Instead, we compute O(1): x.height = max(x.left.height, x.right.height) + 1 at the back of our Insert(v)/Remove(v) operation as only the height of vertices along the insertion/removal path may be affected. Thus, only O(h) vertices may change its height(v) attribute and in AVL Tree, h < 2 * log N.

Try on the example AVL Tree (ignore the resulting rotation for now, we will come back to it in the next few slides). Notice that only a few vertices along the insertion path: {41,20,29,32} increases their height by +1 and all other vertices will have their heights unchanged.

←

→

🕑

Let's define the following important AVL Tree invariant (property that will never change): A vertex v is said to be height-balanced if |v.left.height - v.right.height| ≤ 1.

A BST is called height-balanced according to the invariant above if every vertex in the BST is height-balanced. Such BST is called AVL Tree, like the example shown above.

Take a moment to pause here and try inserting a few new random vertices or deleting a few random existing vertices. Will the resulting BST still considered height-balanced?

←

→

🕑

Adelson-Velskii and Landis claim that an AVL Tree (a height-balanced BST that satisfies AVL Tree invariant) with N vertices has height h < 2 * log2 N.

The proof relies on the concept of minimum-size AVL Tree of a certain height h.

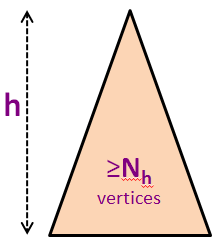

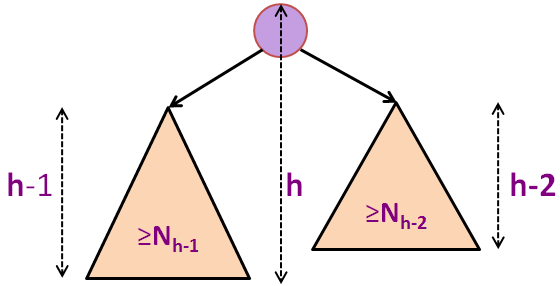

Let Nh be the minimum number of vertices in a height-balanced AVL Tree of height h.

The first few values of Nh are N0 = 1 (a single root vertex), N1 = 2 (a root vertex with either one left child or one right child only), N2 = 4, N3 = 7, N4 = 12, N5 = 20 (see the background picture), and so on (see the next two slides).

←

→

🕑

We know that for any other AVL Tree of N vertices (not necessarily the minimum-size one), we have N ≥ Nh .

In the background picture, we have N5 = 20 vertices but we know that we can squeeze 43 more vertices (up to N = 63) before we have a perfect binary tree of height h = 5.

←

→

🕑

Nh = 1 + Nh-1 + Nh-2 (formula for minimum-size AVL tree of height h)

Nh > 1 + 2*Nh-2 (as Nh-1 > Nh-2)

Nh > 2*Nh-2 (obviously)

Nh > 4*Nh-4 (recursive)

Nh > 8*Nh-6 (another recursive step)

... (we can only do this h/2 times, assuming initial h is even)

Nh > 2h/2*N0 (we reach base case)

Nh > 2h/2 (as N0 = 1)

←

→

🕑

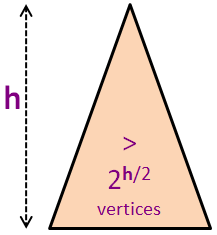

N ≥ Nh > 2h/2 (combining the previous two slides)

N > 2h/2

log2(N) > log2(2h/2) (log2 on both sides)

log2(N) > h/2 (formula simplification)

2 * log2(N) > h or h < 2 * log2(N)

h = O(log(N)) (the final conclusion)

←

→

🕑

Look at the example BST again. See that all vertices are height-balanced, an AVL Tree.

To quickly detect if a vertex v is height balanced or not, we modify the AVL Tree invariant (that has absolute function inside) into: bf(v) = v.left.height - v.right.height.

Now try on the example AVL Tree again. A few vertices along the insertion path: {41,20,29,32} increases their height by +1. Vertices {29,20} will no longer be height-balanced after this insertion (and will be rotated later — discussed in the next few slides), i.e. bf(29) = -2 and bf(20) = -2 too. We need to restore the balance.

←

→

🕑

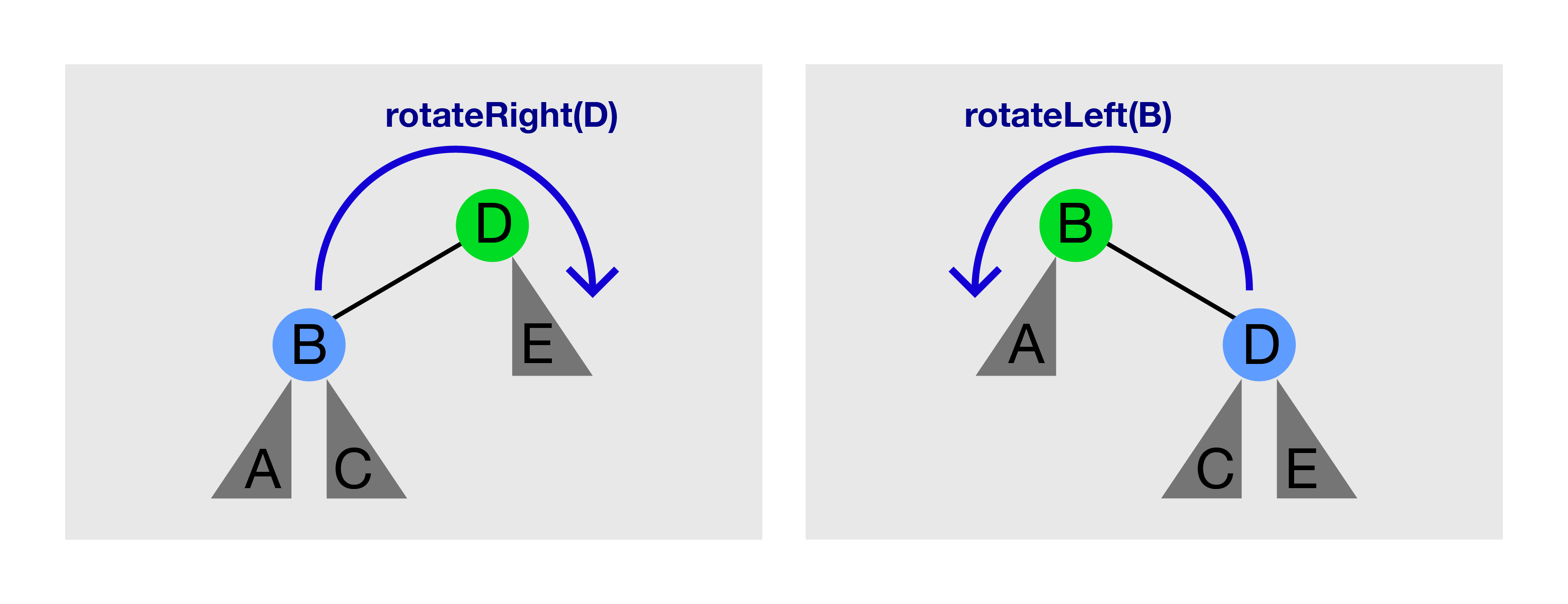

See the picture above. Calling rotateRight(Q) on the left picture will produce the right picture. Calling rotateLeft(P) on the right picture will produce the left picture again.

rotateRight(T)/rotateLeft(T) can only be called if T has a left/right child, respectively.

Tree Rotation preserves BST property. Before rotation, P ≤ B ≤ Q. After rotation, notice that subtree rooted at B (if it exists) changes parent, but P ≤ B ≤ Q does not change.

←

→

🕑

BSTVertex rotateLeft(BSTVertex T) // pre-req: T.right != null

BSTVertex w = T.right // rotateRight is the mirror copy of this

w.parent = T.parent // this method is hard to get right for newbie

T.parent = w

T.right = w.left

if (w.left != null) w.left.parent = T

w.left = T

// update the height of T and then w here

return w

←

→

🕑

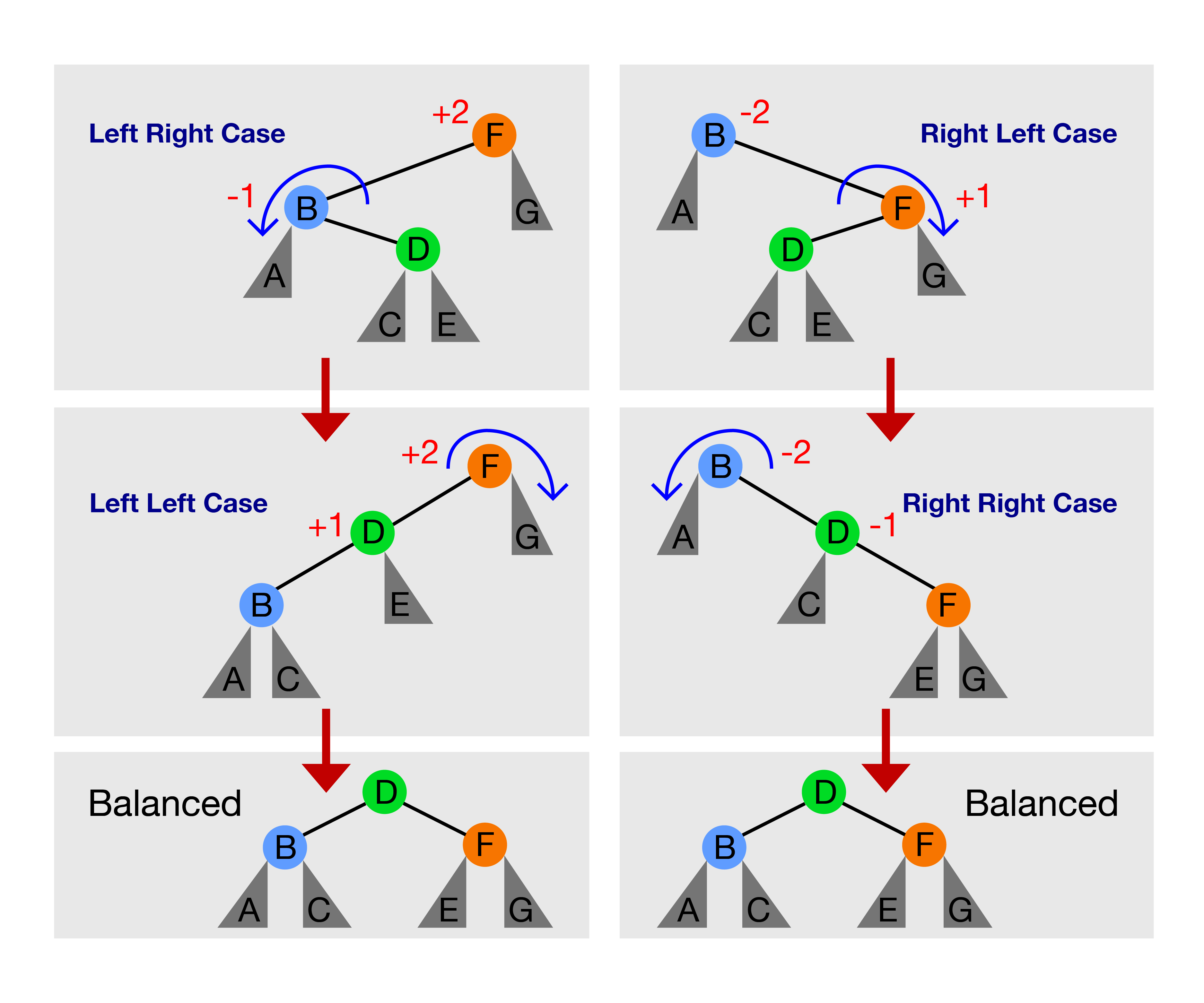

Basically, there are only these four imbalance cases. We use Tree Rotation(s) to deal with each of them.

←

→

🕑

- Just insert v as in normal BST,

- Walk up the AVL Tree from the insertion point back to the root and at every step, we update the height and balance factor of the affected vertices:

- Stop at the first vertex that is out-of-balance (+2 or -2), if any,

- Use one of the four tree rotation cases to rebalance it again, e.g. try on the example above and notice by calling rotateLeft(29) once, we fix the imbalance issue.

Discussion: Is there other tree rotation cases for Insert(v) operation of AVL Tree?

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

- Just remove v as in normal BST (one of the three removal cases),

- Walk up the AVL Tree from the deletion point back to the root and at every step, we update the height and balance factor of the affected vertices:

- Now for every vertex that is out-of-balance (+2 or -2), we use one of the four tree rotation cases to rebalance them (can be more than one) again.

The main difference compared to Insert(v) in AVL tree is that we may trigger one of the four possible rebalancing cases several times, but not more than h = O(log N) times :O, try on the example above to see two chain reactions rotateRight(6) and then rotateRight(16)+rotateLeft(8) combo.

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

We will end this module with a few more interesting things about BST and balanced BST (especially AVL Tree).

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

←

→

🕑

For a few more interesting questions about this data structure, please practice on BST/AVL training module (no login is required).

However, for registered users, you should login and then go to the Main Training Page to officially clear this module and such achievement will be recorded in your user account.

←

→

🕑

We also have a few programming problems that somewhat requires the usage of this balanced BST (like AVL Tree) data structure: Kattis - compoundwords and Kattis - baconeggsandspam.

Try them to consolidate and improve your understanding about this data structure. You are allowed to use C++ STL map/set, Java TreeMap/TreeSet, or OCaml Map/Set if that simplifies your implementation (Note that Python doesn't have built-in bBST implementation).

←

→

🕑

The content of this interesting slide (the answer of the usually intriguing discussion point from the earlier slide) is hidden and only available for legitimate CS lecturer worldwide. This mechanism is used in the various flipped classrooms in NUS.

If you are really a CS lecturer (or an IT teacher) (outside of NUS) and are interested to know the answers, please drop an email to stevenhalim at gmail dot com (show your University staff profile/relevant proof to Steven) for Steven to manually activate this CS lecturer-only feature for you.

FAQ: This feature will NOT be given to anyone else who is not a CS lecturer.

You have reached the last slide. Return to 'Exploration Mode' to start exploring!

Note that if you notice any bug in this visualization or if you want to request for a new visualization feature, do not hesitate to drop an email to the project leader: Dr Steven Halim via his email address: stevenhalim at gmail dot com.

←

🕑

Please rotate your device to landscape mode for a better experience

Please make the window wider for a better experience

Create

Search

Insert

Remove

Predec-/Succ-essor

Tree Traversal

>

Source: https://visualgo.net/en/bst

0 Response to "Draw Binary Tree Diagram Online"

Post a Comment