Gray Scale Japanese Sakura Tree Moon Drawing

Reading time: 20 minutes

"If we study Japanese art, we see a man who is undoubtedly wise, philosophic, and intelligent who spends his time doing what?," wondered 35-year-old Vincent van Gogh in a September 1888 letter to his brother, Theo. Admiring the intrinsic wisdom of the Japanese artist who is unanchored from the dispassionate, reasoning world of scientific ideas and the false urgency of politics, the Dutch artist goes on to ask whether his Japanese counterpart is busy "studying the distance between the earth and the moon" or "Bismarck's politics," a reference to Otto von Bismarck, the first Chancellor of the German Empire, arguably the most powerful man in Europe at the time.

"No," is Van Gogh's simple and unequivocal answer to both of these questions, before making clear the source of wisdom that engenders the Japanese artist's philosophy and aesthetics:

"He studies a single blade of grass. But this blade of grass leads him to draw every plant, then great views of the countryside in every season, then animals, then human figures. So he passes his life, and life is too short to do the whole. Come now, isn't it a true religion that these simple Japanese teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers? And we wouldn't be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful, and it makes us return to nature, despite our education and our work in a world of convention."

That "single blade of grass" (un seul brin d'herbe) – though laden with metaphorical symbolism – was a literal reference to the title of a drawing Van Gogh had seen in the first issue of the magazine Le Japon artistique, May 1888, which his brother had sent him in Arles. According to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the artist took such a great liking to this study of grass that, months later, he pinned it to the wall of his room in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

To the Western eye Japanese artworks appear simple and unfinished, with symbols that, once exported, lack the potency and relevance of their original environment. But what to us might be just a sketch or study, for Van Gogh was a lesson in acknowledging and honoring the passing beauty of life. In the same letter to Theo, the Dutch artist doesn't hesitate to compare Japanese woodblock prints to the works of the great European masters: "Whatever one may say, for me the more ordinary Japanese prints, colored in flat tones, are admirable for the same reason as Rubens and Veronese."

The "ordinary Japanese prints" were called ukiyo-e, which poetically translates as "pictures of the floating world." Contrary to popular belief, they weren't the creation of just one person – the artist – but part of a tight-knit collaboration between the artist drawing the image on paper, the carver who meticulously carved the design into a woodblock, and the printer who used the woodblock to reproduce and color the final image. The artist's original design would always get destroyed during the process – a sacrifice offered on the shrine of creation – only to be later transformed, replicated and enhanced, its beauty multiplied by the dedicated hands of collective craftsmanship.

Although Van Gogh had first discovered the marvels of Japanese art in the Belgian city of Antwerp, it was during his Parisian years living with Theo when this curiosity turned into a most-inspiring, blazing passion which ended up fueling his creative fire. For two years the Van Gogh brothers avidly collected Japanese prints, hundreds of them, building a remarkable collection. Most of them were bought from the gallery of Siegfried Bing, a famed German-French art dealer who imported Japanese and Chinese art objects. As it so happens, Bing was also the publisher of Le Japon artistique.

To say that Japanese prints influenced Van Gogh's art would be a gross understatement. But he wasn't the first artist to benefit from this influence either. Almost two decades earlier, when the exoticism of Japan started sweeping across the Old Continent and influencing European art – a phenomenon coined as Japonisme – Édouard Manet shocked the world with Olympia, the reclining nude of a prostitute posing as Titian's Venus of Urbino. Beyond the unapologetically controversial subject matter, the flattened painting with blocks of color and an unfinished look carried the trademarks of Japanese prints.

Impressionists quickly followed suit, enchanted with the Japanese artists' groundbreaking techniques on perspective and composition, at odds with the dull rules of the French Academy. Edgar Degas, for one, in paintings such as The Ballet Class (previously discussed here) masterfully resorted to dramatic diagonal lines, a slightly elevated vantage point and cropping artifices to suggest movement and dynamism for his ballerinas, all while making the viewers feel like they were physically present in the room.

These well-treasured, exotic woodblock prints may have been a key ingredient to many artists' maturation and creative blooming – and they certainly were for Van Gogh – but the philosophy they carried also alleviated, to some degree, the suffering Vincent endured during his last months, arguably the bleakest period of his life.

It was while confined in the psychiatric hospital Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in Saint-Rémy, where he had voluntarily committed himself after multiple nervous breakdowns, that Van Gogh completed some of his most quintessentially Japanese paintings. These close-up, tightly cropped artworks, patiently zooming in on the fragile beauty of life to reward us with awe and breathtaking wonder, are richly infused with the philosophy the artist so admired in Japanese printmaking.

Irises, for instance, painted in May 1889, during the very first week of Van Gogh's hospitalization, is a vibrant, visual hymn to ever-passing beauty. In an organic unfolding of effervescent, barely-contained swirling lines, silky blue irises are humming, twisting and turning in nature's swaying tempo. Fragile as a flower may seem, it can withstand so much more than we think possible. Compositionally, the asymmetrical display of the irises and the way the foreground has been cropped recount previous innovations the Impressionists had seized from Japanese printmakers.

Amidst all, one white iris stands apart – not just in color, but also in the way its petals are straddling both the sprawling blue irises and the marigolds in the background, like an artist living on the fringes of two worlds at once. Alone among its peers, alone among its community.

Offering his wholehearted attention to every petal, to every blade of grass, to every swirling brushstroke, Van Gogh was living the Japanese philosophy, reaching outside himself to take in life's wonders, one exquisite, small detail at a time.

"It is one of your good things. It seems to me that you are stronger when you paint true things like that," Theo wrote to his brother after seeing Irises. He was right. Nature had become Vincent's refuge during those troubling times, when everything seemed to be slipping away from him.

Eight months later, shortly after Theo named his newborn infant Vincent Willem in honor of his brother, the Dutch artist painted Almond Blossom as a gift to Theo and his wife, Jo. Astonishing in their simplicity, the large blossom branches against a serene blue sky signify hope and the arrival of spring. When looking at them, it's hard not to be reminded of the woodblock prints created by Japanese print-maker Utagawa Hiroshige – one of Van Gogh's major inspirations – who often depicted flowers and birds up close with simple backdrops.

The Dutch artist was so taken with Hiroshige's prints that he even copied some of them, such as Flowering Plum Orchard and Bridge in the Rain.

Van Gogh would be neither the first, nor the last person to seek refuge in the soothing simplicity of nature. A few decades later across the Atlantic, American artist Georgia O'Keeffe, who struggled with prolonged bouts of depression repeatedly during her lifetime, would also find solace in the delicate details that nature had to offer. Her macroscopic flower paintings created in the first half of the 20th century have long been misconstrued as depicting female genitalia, a trope popularized by her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who was also an art dealer.

But O'Keeffe vehemently denied this crude, Freudian interpretation of her work. In her own words, written in the forward to a 1939 exhibition catalog, the American artist espouses the underlying creed of her art – transposing the microscopic to a scale so large that it cannot be overlooked any longer:

"A flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower — the idea of flowers. You put out your hand to touch the flower — lean forward to smell it — maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking — or give it to someone to please them. Still — in a way — nobody sees a flower — really — it is so small — we haven't time — and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. […] So I said to myself — I'll paint what I see — what the flower is to me but I'll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it — I will make even busy New-Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers."

It is rather ironic that in order to see – that is to really see and wholeheartedly pay attention to what lies before us – O'Keeffe transfigures the concrete into almost-abstraction, the essence of her subjects transcending line, shape and color in a deliriously beautiful and vibrant attempt to grasp the ineffable.

***

Centuries before mindfulness became a popular social media wellness mantra, what to Western artists might have been a concerted effort to escape one's limiting individuality and ceaseless ruminations, or even a deliberate process to enhance one's creativity, to the Japanese it was a philosophy gracefully infused in everyday life.

Van Gogh couldn't be more right when he compared the profound spirituality with which this wise nation reveres nature in all its infinitesimal splendor to "true religion". After all, Shinto – Japan's traditional religion – is populated by spirits and deities called kami which reside in rocks, trees, rivers and mountains. Just as importantly, Buddhism, imported in the late-6th century and deeply entrenched in the Japanese culture, brought the belief in the impermanence of life, everything being transient and subject to change. Or, as Heraclitus of Ephesus, the Greek philosopher contemporary with the Buddha, sagely remarked (quoted by Plato in Cratylus): "You cannot step into the same river twice."

It's no wonder then, given the Japanese people's spiritual love of nature and their serene forbearance of life's never-ending ebb and flow, that the celebration of seasonal change is a most defining, sacred and enthusiastically cherished part of their culture. Every year, this ethos peaks during the cherry blossom viewing festival, called hanami.

In one of the short waka poems he wrote while living at the Imperial Bodyguards' headquarters in the early-13th century, famed poet Fujiwara no Teika gives us a glimpse of this centuries old tradition, as cherished then as it is today:

"Spring passes and

The royal visit's here – a blizzard

Of blossom shading,

Falling – and me ageing –

Do you think of me kindly?"

To condense so much imagery in just a few words – addressing longing, old age and the striking visual of cherry trees shedding the whiteness of their blossom – is a lesson in the most delicate craftsmanship, allowing nature to flow freely between the lines and reveal its wisdom gently, like a flower in bloom.

Almost seven centuries later, Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige would also heed this lesson. Cherry trees are frequently popping up in Hiroshige's prints, whether they're solitary guardians of the riverbanks or gleeful companions to the courtesans in the overcrowded pleasure districts. They even show up in ancient legends or as the backdrop for lovemaking couples in shunga – the widely popular, erotic genre of ukiyo-e, ultimately banned in the early 1900s. Shunga literally translates as "pictures of spring," with spring being a euphemism for sex. And what better symbol for the zest and rejuvenation this season brings than the cherry trees' full blossom?

Unlike his more famous contemporary Katsushika Hokusai, Hiroshige portrays late-19th century Japan as it is, without resorting to compositional contraptions to emphasize the spiritual. He lays before us a world that indulges the senses and bewitches the eye. Beauty is to be found in the ephemeral, in the minutiae of everyday life. But make no mistake – Hiroshige was no realist either. While his art was rooted in the countless sketchbooks he filled during his travels throughout Japan, he used the sketches as blueprints to be further enhanced by his compositional flair and the glowing warmth that only the power of memory and imagination can provide.

Cherry Trees in Full Bloom at Arashiyama (c. 1834) is perhaps one of Hiroshige's most stunning prints, a poignant illustration of the Japanese aesthetics and culture so revered by European artists. As the Ōi river flows along the northeastern corner of Kyoto, Japan's ancient capital, cradling on its waves a raft with two cargo men, soft petals are falling like snow from the arching cherry trees along the riverbank. It is a visual ode to transience, wrapped in fluid movement and smooth gentleness. Everything – from the wandering river to the blossoming trees and the delicate, dissipating smoke rising up from the raft – echoes panta rhei, Heraclitus' aphorism and philosophy of change. Everything flows.

The sense of movement is masterfully captured by Hiroshige through the use of diagonal lines, many of them parallel to the oblique Ōi river and its left bank. Others disrupt the flow and bring attention to the men on the raft and the heaviness of the cherry blossoms, the flower-laden trees leaning their branches over the river and intersecting its lines almost perpendicularly.

With no horizon line, and a bird's-eye view, we get to witness the scene quite intimately. There is a larger-than-life feeling rippling from the wide, unswerving river, which dominates the landscape and takes up half of the composition. It's hard not to be reminded of the major rivers that nourished ancient civilizations; whether the Nile in Egypt, Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia, or the Indus in the Indus Valley, rivers have been the veins carrying life, knowledge and riches throughout history. The awe is further amplified by the striking contrast of the deep blue water with the white and pink of the cherry tree flowers, Ōi appearing as a cosmic river lit by constellations of scattered petals. No wonder Van Gogh felt so inspired by the visual poetry of this floating world.

More than two decades later, in his series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, Hiroshige returns to the blooming cherry trees – this time in Koganei, a city west of Tokyo – using a vertical format to emphasize their grandeur.

Koganei in Musashi Province offers us an unexpected sight captured with the unmistakable flair of an experienced photographer. At first, the eye wanders from the towering cherry tree, too large to be contained in one frame, towards the river rapids cascading in the far distance. But serving as an ingenuous viewfinder is a split in the old cherry tree trunk in the foreground through which we can see Mount Fuji, Japan's most sacred symbol. Its snow-capped cone barely contrasts with the fading hues of the evening sky.

Less dramatic, but perhaps inspired by the exact same spot, is The Embankment at Koganei in the Musashi Province, which makes us appreciate the composition of the previous print even more. The view is significantly more serene here, being balanced by horizontal lines stacked like geological layers. We can also see Mount Fuji clearly against the evening sky, its edges flanked by cherry tree flowers in the foreground and mid-distance.

Like a wound that no amount of time or love can heal, the cavity of the cherry tree in the foreground is just as touching as those in Koganei in Musashi Province. Wasn't it Leonard Cohen who sang "there's a crack in everything, that's how the light gets in?" For beauty without vulnerability is not beauty at all.

Other vistas of the province of Musashi include View of Mount Fuji from Koshigaya in which two saplings are timidly blossoming, Evening Glow at Koganei Border where the cherry trees adorn the local community with their splendid floral crowns, and the exquisite fan print The Upper Reaches of the Tama Water Supply Flowing through the Koganei Embankment.

There is so much unfolding in the last piece. From the contemplative woman with her back turned to us to the silhouette of Mount Fuji in the distance and in between them the blue river lazily stretching towards the dusk orange-red sky with its fluttering flock of spring birds. But the print only comes alive thanks to the rows of cherry trees in full blossom lining the mossy riverbanks, their reflections awash in the nostalgic blue of the waters like a beautiful midnight dream one barely remembers by morning.

***

Granted, it is perhaps too easy to gush over the cherry tree blossoms when they're embellishing moments of solitude amidst virgin landscapes. Luckily for us, however, they also pop up in Edo – present-day Tokyo – in the notorious Yoshiwara red-light district.

Although prostitution could only be practiced in certain restricted areas called pleasure districts, in the late-19th century this trade was legal in Japan, due to the Japanese people's rather lax attitude towards sex. There are numerous accounts of respectable Japanese families eager to present their extensive collections of erotic prints – often proudly hung on walls – to the prude, squirming Westerners crossing their thresholds.

It was under these auspicious conditions that courtesans came to flourish during the Edo period (1603-1868). Highly esteemed for their beauty, intelligence, artistry and fashion style, the elite Japanese women of pleasure were called oiran. The notoriety and admiration they received within the red-light districts and society at large was, in no small part, due to the ukiyo-e artists who frequently idealized and depicted them in their art, particularly in shunga. And few artists portrayed them better or with more passionate devotion than Kitagawa Utamaro.

Lovers in the Upstairs Room of a Teahouse is one of Utamaro's most celebrated prints and also one of the gems of shunga, where the eroticism courses electrically through entwined and overlapping lines and limbs. Unlike most erotic in-your-face prints which graphically display enlarged genitalia, here the sexual tension is far more subtle, reaching an unlikely peak around the woman's nape, wonderfully contrasted with the blackness of her hair. The lovers tenderly hold each other with surprisingly tiny hands.

Although her simple hairstyle and attire rule her out as an oiran, the woman depicted by Utamaro could very well be a prostitute. Teahouses used to serve as motels where clients could rent private rooms for a few hours. The ambiguity of the relationship, consumed in such an unlikely place, only increases the sexual tension between the pair. And if this rich imagery wasn't enough, the print is accompanied by a very suggestive, poetically veiled text:

"Its beak caught firmly

In the clam shell,

The snipe cannot

Fly away

Of an autumn evening"

Hiroshige, for his part, was buoyed by the joy and bohemian atmosphere of Edo's pleasure district where courtesans, common prostitutes, tea-shop girls and geishas mingled with clients, artists, actors, dancers and musicians almost indiscriminately, in a potpourri of intoxicating sensuality and multifaceted artistry.

To look at Hiroshige's depictions of Yoshiwara in springtime means to believe in his vision of the pleasure district as an idyllic place where beauty, lust and happiness can be easily bought. It means to get swayed by the courtesans' lavish costumes and intricate hairstyles – which would often start fashion trends sprawling throughout Edo and beyond – in believing that these women not only desired and had full autonomy in choosing this lifestyle, but that they celebrated it with all its perks, expensive gifts and the social status it provided.

In his Yoshiwara prints (Spring Scene at Naka-no-chō in the New Yoshiwara, Cherry Blossoms at Night in the Yoshiwara and Cherry Blossoms at Night on Naka-no-chō in the Yoshiwara) we get to see lively processions of the various characters weaving the social tapestry of the district, at different times of the day.

As they parade on Naka-no-chō, the main boulevard in Edo's pleasure quarter, flanked by teahouses and crowded with clients, street vendors and drum players, we can spot the courtesans by their complex hairstyles (the higher the number of combs in their hair, the higher their status), their colorful, silk kimonos with obi tied in front and the attendees who coalesce around them.

Cute, little girls hold the women's long trains, displaying intricate hairstyles themselves while walking on wooden platform sandals (okobo) and wearing matching outfits. Or they're hidden by umbrellas, scattered like mushrooms springing forth after the rain. The reality, however, was much, much grimmer. Called kamuro, the girls, who were brought into service extremely young – between 5 and 9 years old – were training to one day become courtesans too, running errands for their elder sisters whom they idolized.

During springtime cherry blossom viewing was a much awaited event in Yoshiwara. The trees would be transplanted there as soon as they bloomed, drawing in increasing crowds of visitors who could delight in the passing beauty of the cherry flowers. The sight was even more astonishing at nighttime, when the district got animated and the ethereal white of the flowers contrasted with the darkness of the sky, soft petals glowing with the fluorescence of jellyfish beneath the ocean waters.

But the beauty of the cherry tree blossoms never lasted. And neither did the courtesans' fame. Perhaps the curse was hiding in plain sight under the guise of their name. Oiran, written in kanji, is made up of two characters: 花 "flower" and 魁 "leader". Like cherry tree flowers they bloomed and blossomed, drawing crowds of visitors eager to take in their beauty. Like cherry tree flowers, they too, faded and withered, by the mid-1950s being reduced to nothing but a story half-whispered in the dusty pages of history books.

While Hiroshige seized on the festive atmosphere on Naka-no-chō, understanding its touristic and commercial appeal – people from all over Japan traveled to Yoshiwara, and his prints served as postcards – the Japanese artist couldn't have been completely oblivious to the sad lives and shattered dreams squashed between the quarters' walls. At least, that is the impression he leaves in Asakusa Ricefields and Torinomachi Festival, in which he offers a rare, melancholic glimpse of the private room of a courtesan during the busiest day of the year: the Torinomachi Festival.

On that occasion, the pleasure district was open to everyone and each courtesan was required to take on a client. But despite the hustle and bustle of the day, and the lively procession taking place on the rice fields in the far distance, the courtesan's quarter looks not much different from a prison cell, with the antiseptic charm and sensuality of a hospital room. Behind a wooden-barred window lie some of her most basic trade utensils – a mouth-rinsing bowl and a used towel on the sill, while to the left, poking out from behind a folding screen, are a set of kumade hairpins (most likely a gift from her client) and a set of tissues known as onkotogami, "paper for the honorable act." With its back turned to us, a white cat is looking at the beautiful but out-of-reach landscape beyond the wooden bars, with Mount Fuji against an evening sky. Hiroshige, no doubt, must have understood that the glamour of Yoshiwara was just a façade.

***

What's striking about these prints – especially those of Naka-no-chō – is how well Hiroshige had mastered the Western perspective, the system which allows lines to converge to a vanishing point and project the illusion of depth onto bi-dimensional planes. Although Europeans admired ukiyo-e prints for their quintessential flat Japanese style, and drew inspiration from them, what's lesser known is that Japanese artists were also inspired by their foreign counterparts.

It wasn't until the 19th century that ukiyo-e artists started using perspective to gain the illusion of three-dimensional space in their works, yet it's hard to believe that this was a breakthrough for them – after all, four centuries had passed since the Italian Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi had done the first picture espousing the revolutionary system. But as commerce flourished between Japan and France, this open attitude must have reverberated throughout the art world, two different cultures complementing and feeding off each other in new and unexpected ways.

Prussian blue – a dark blue pigment discovered in 1706 in Berlin – was another European import that came to redefine ukiyo-e woodblock prints almost a century later. Cheaper than the well-prized lapis lazuli, but more enduring than other analogous pigments, Prussian blue became a staple of ukiyo-e, due to the fact that the color kept its vibrancy despite repeated reprints. It's hard to imagine Hokusai's famous The Great Wave off Kanagawa without this pigment.

To attempt to separate authenticity stemming from one's cultural heritage from the rippling and unpredictable effects of creativity – which knows no bounds, has no country, and bows to neither kings, nor queens – is to navigate treacherous, abyssal waters bearing the appearance of mere ponds. Try as we might, creativity cannot be disassembled into neatly packed columns in a scientific catalogue, each observation stemming from a precise point of origin. Neither can beauty be determined like a variable in a polynomial equation.

But there is a tendency, even among the most sensible Western artists, to try to possess and dissect the beautiful and the ephemeral with the scalpel of objectivity and the sharp blade of critical thinking. Whether it was Georgia O'Keeffe collecting animal skulls and sun-bleached bones in the desert of New Mexico, Vladimir Nabokov pinning butterflies for his extensive collection of Lepidoptera, or young Emily Dickinson pressing soft flowers between the pages of her herbarium, Western artists had often found themselves torn between the poetry of the fleeting moment and their scientific curiosity, eager to hold, label and quantify every small, earthly delight.

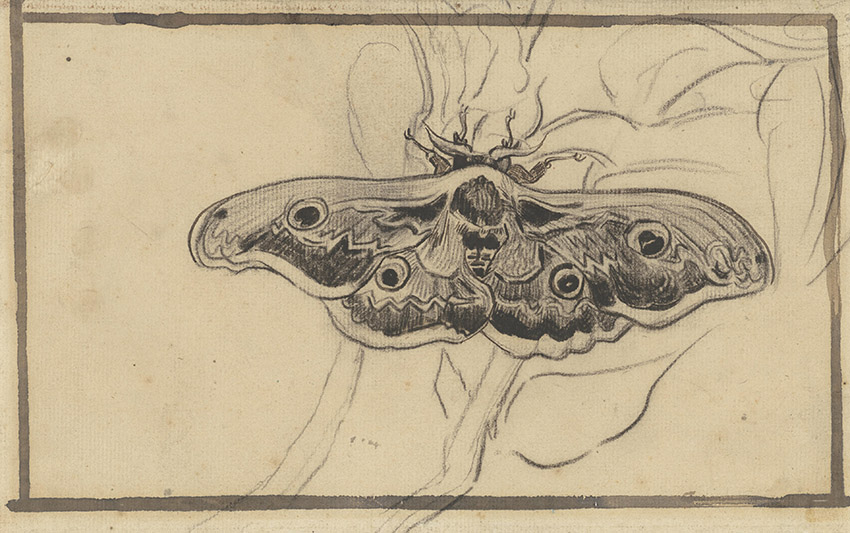

Three decades after Utagawa Hiroshige had passed away, his legacy still rippling across oceans and reaching the shores of the Mediterranean in the south of France, an awe-struck Van Gogh was battling with the same dilemma, vacillating between his love of nature and his instinct to possess it. Walking through the garden at the asylum in Saint-Rémy in late-May 1889, the Dutch artist came across a giant peacock moth with an astonishing coloration of "black, grey, white, shaded, and with glints of carmine or vaguely tending towards olive green." Mistaking it for a "death's-head moth," he drew a sketch of it, lamenting to Theo that "to paint it I would have had to kill it, and that would have been a shame since the animal was so beautiful."

Later, however, Van Gogh changed his mind, and ended up painting the faux "death's-head moth." To do so, he blended in his previous observational sketch with the vivid memory of the insect, filling in the gaps with the thick brushstrokes of his imagination, just like Hiroshige had done for his woodblock prints. The lesson had been learned. Somehow, the Dutch artist was living the very philosophy he revered, by honoring the passing beauty of life.

One year later, just 30 km north of Paris in Auvers-sur-Oise, a bullet lethally perforated his stomach. In a cruel irony of fate, Van Gogh's clemency didn't apply to his own life – the most beloved artist of our time had, most likely, committed suicide.

***

Cherry blossoms don't last for more than two weeks. A giant peacock moth lives for no more than nine months, enough for a human fetus to grow in its mother's womb. Whether she will live 37 passionate years, like Van Gogh, cherish 61 springs like Hiroshige, or be fortunate to die of old age at 88 like Hokusai, is anyone's guess. Everything flows, is what the ukiyo-e pictures of the floating world teach us, burdened by their own impermanence.

There is a ticking clock now running for these woodblock prints, their paper too frail to withstand life's warm breath and shimmering light. Kept on life support in dark, humid rooms away from prying museum crowds, they only resurface once every few years, with each new public display unveiling them as more damaged and less vibrant than before, crumpling and fading under the weight of time. They too, shall pass, like you and I, like artists' lives and cherry blossoms, but not before they leave their mark behind, footprints of a world in passing.

Source: https://artschaft.com/2019/04/16/van-gogh-hiroshiges-cherry-blossoms-and-the-impermanence-of-life/

0 Response to "Gray Scale Japanese Sakura Tree Moon Drawing"

Post a Comment